Uhila Nai

Our Ancestors are Our Archives

The live documentation of my ancestors

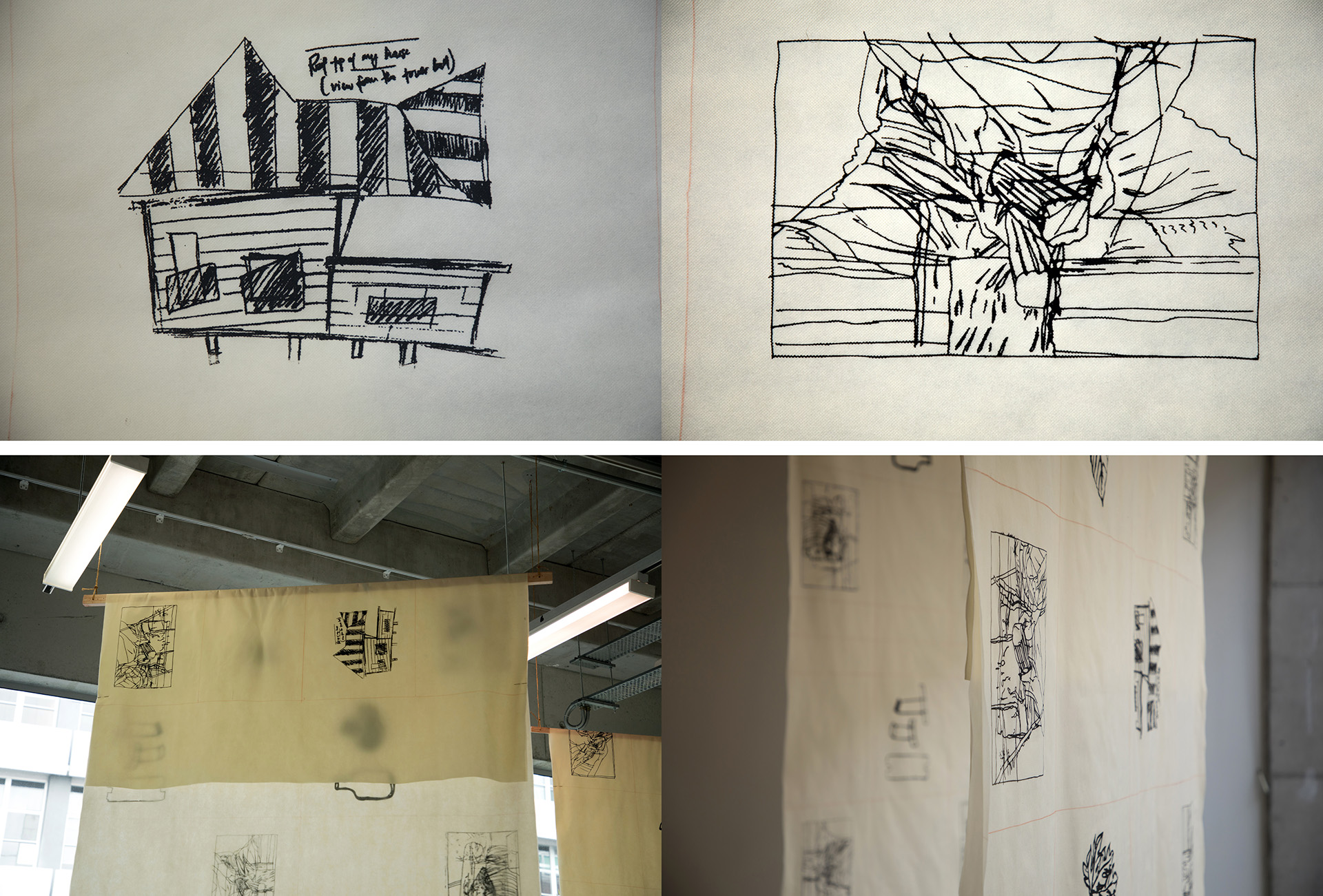

This project derives from a personal interpretation of lea mu‘a (old saying) and lea Faka-Tonga (Tongan language), which is translated into kupesi symbols to produce a contemporary Tongan ngatu. The research utilises visual language of ancient Tonga and today‘s lea Faka-Tonga to emanate tala tukufakaholo with my family, a collection of knowledge about the history of hingoa fakafamili, tupu‘anga, and manatu about my Nena and myself. This tala tukufakaholo tātānaki(to collect) reflects not only the past tala tupu‘a (myth or legend handed down from ancient times) but also the space the ngatu occupies. It is present; for instance, in my art practice, it relates to the notion of learning through listening, observation and doing with a focus on how this mode of practising can position itself in a contemporary space of artmaking. The physical materials used are natural materials from the niu, the paongo, feta‘aki, and fau – along with methods and processes of ngatu and kupesi making; tui kupesi and to spread out the kupesi onto the papa koka‘anga.

Family Memories: capturing stories from different time-lines within the Tongan traditional crafts of ngatu (decorated barkcloth) making and kupesi (embroidered stencil) design explores the transmission of visual vocabulary into kupesi design as a way to understand our fine arts as living archives of our histories. The histories, stories, and memories; the process of naming and language has become a key concept and an inherent part of the knowledge that formed this research. The concepts of knowing, the idea that there is knowledge in memory have influenced me to choose what has been gifted to me as a responsibility to do the project.

My practice has been influenced and inspired by my Nena, ‘Ana, the late ‘Ana Va‘inga Pautā (born Kanongata‘a), who was also a mother figure to me. My Nena raised me in the small village of Pelehake on the East-side of Tonga from 1998 until the end of 2011. Back home, most children are known to learn their culture through observation, listening, and doing. It was an obligation. The parents, the family, and the community ensure that all children have the opportunity to express their culture. As time passed by, I started to learn the Tongan traditional crafts my Nena was an expert in, particularly the art of ngatu production. Nena had her ways of transferring and passing knowledge onto me through old processes, methods, and actions of making. As a knowledge-holder herself, she demonstrated and taught me traditional crafts using a variety of approaches – nimamea‘a koka‘anga, making of lolo Tonga, storytelling, and through action. For eleven years of being beside her, I was blessed and lucky to be able to learn and gain new knowledge every day. The amount of experience she shared with me now has a home, which is being transmitted into form through this research project and my art practice in general.

My project is not only influenced by my Grandmother but also family mentors – family and the elders from Pelehake, especially those who were in the same koka‘anga group as my Nena. Throughout this research project, I visited Pelehake several times for extended stays of 6-8 weeks. Even though my grandmother is no longer with me, the knowledge holders from my community have inspired the project through their ways of saying, “it is good to see you doing what your Nena always make” or “it is respectful of you trying to learn the craft of kupesi making” or “I am happy to see you making kupesi because us, we are getting older and we can’t make kupesi anymore.” As they spoke, it recreated a memory from the past and fakakoloa‘aki as they shared their words with me. In many ways, it felt like they were not only giving me words of encouragement but had “gifted responsibilities to me” rather than saying, “you have to do it.”

This project works through a different type of knowledge, which has been gained over a different time-line. They consist of varieties of knowledge passed down from elder generations, my grandmother, women in the community, mentors, and family members. The multiple voices pass down to one voice, which is now manifested in my project through many approaches. Throughout the making and the background research of the project, I found myself going back and forth between the past and present, every time I learned new knowledge. In ways that I speak and tell stories using ancient Tongan words that my ancestors used in their time or sharing a story as if I was there at the exact moment and had witnessed what happened. I am often in a position where I do not realise it myself as I travel back in time, revealing stories and histories that I have been told as a kid through my making. To consider a reason why – it is because I am named after my Nena’s mother, ‘Uhila (Lahi) Tu‘ipulotu and family often refer to me as the mother, grandmother, or twin, if only because of my name. In ways, not previously understood or realised, I now see myself going back and forth, in part because of the name, ‘Uhila, and in honour of becoming a knowledge holder. In "The forked centre: duality & privacy in Polynesian space & architecture" (Albert Refiti, 2008, 99), he discusses the notion of ‘knowing who you are in relation to the fanua (landscape) and tupu‘aga (ancestors).’

Refiti states,

This knowing/placing who you are involves the understanding that your body, your being is woven flesh, a gene-archaeological matter made of ancestors/land/community/family. Therefore, your body does not necessarily belong to you as an individual. Because you weave from the flesh of the dead, your body belongs to the ancestors, to your fanua, the place of birth, and the community that shaped and cared for you. As for the consequence of your ‘being there’ allows (these bodies of ancestors) to be present there/here too.1

Through my practice, I travel and collect with a methodology of the past, the methods of the present, and the context of the future, knowing that every time I research about my ancestors, my body belongs to my ancestors, depending on the past that I am interested in it. For example, back home in Tonga, I research the craft of ngatu and kupesi. Through time, I can learn the knowledge and processes thanks to the conversation that my body is continually having with the women in my family, my Nena, and my community. What they offer is a space of knowing. Every time I make, they are always in me, because I am living in the presence of my ancestors. The flesh of the dead weave through generations as they (we) become the archives for our living history.

‘Uhila Mo-e-Langi Nai

November 2020.

-----------

1. Albert Refiti, “Alternative: An International Journal of Indigenous Scholarship, (2008), 99.